Stories

First-hand experiences of meditation and spirituality.

'You have to be like a warrior and fight'

Mahiyan Savage San Diego, United States

'When you perform for me, always choose devotional songs.'

Gunthita Corda Zurich, Switzerland

In the Whirlwind of Life

Pradeep Hoogakker The Hague, Netherlands

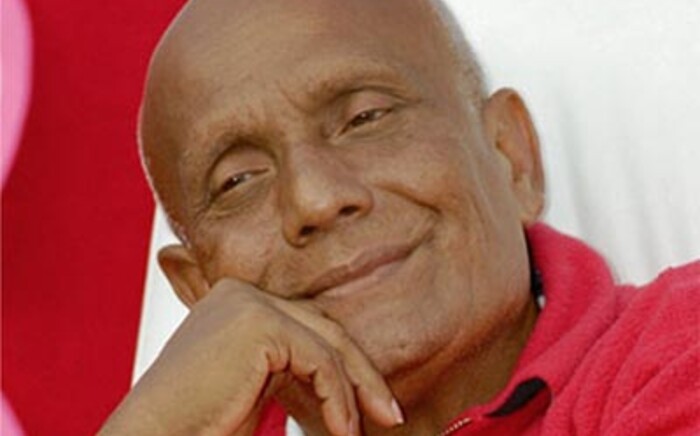

My life with Sri Chinmoy

Namrata Moses New York, United States

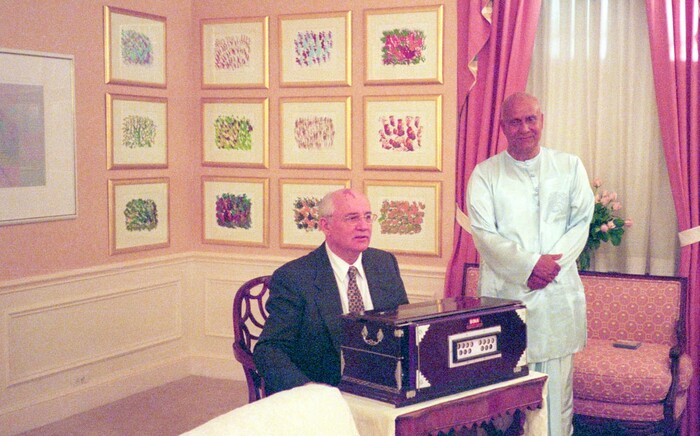

President Gorbachev: a special soul brought down for a special reason

Mridanga Spencer Ipswich, United Kingdom

Reflections on meditation

Janaka Spence Edinburgh, United Kingdom

The happiest I've ever been

Gabriele Settimi San Diego, United States

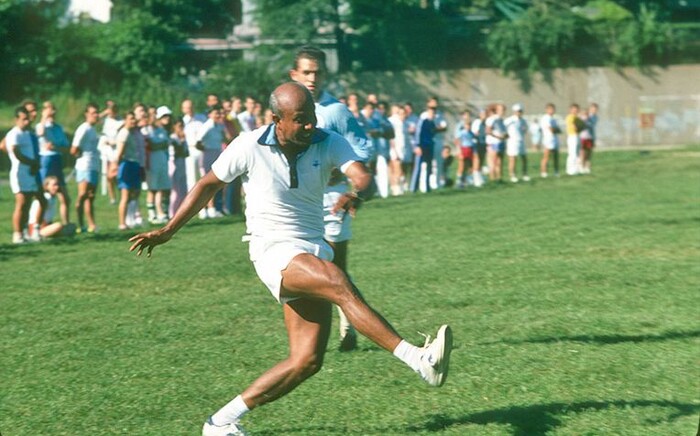

Learning to love songs ever more

Patanga Cordeiro São Paulo, Brazil

Listen to the inner voice

Vidura Groulx Montreal, Canada

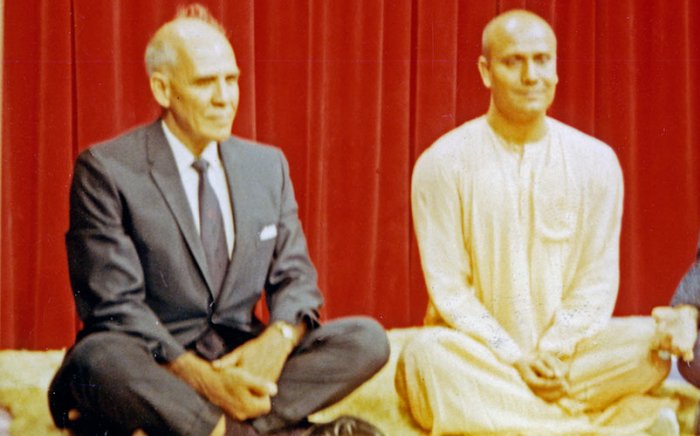

Our Guru becomes the perfect disciple

Devashishu Torpy London, United Kingdom

Celebrating birthdays at Guru's house

Devashishu Torpy London, United Kingdom

The Impact of a Yogi on My Life

Agni Casanova San Juan, Puerto Rico

Having a Spiritual Teacher

Preetidutta Thorpe Auckland, New ZealandSuggested videos

interviews with Sri Chinmoy's students

What meditation gave me that I was missing

Purnahuti Wagner Guatemala City, Guatemala

Things I have learnt from the spiritual life

Sanjay Rawal New York, United States

How can we create harmony in the world?

Baridhi Yonchev Sofia, Bulgaria

My favourite part of Sri Chinmoy's path

Muslim Badami Auckland, New Zealand

Winning the Swiss Alpine Marathon

Vajin Armstrong Auckland, New Zealand

My well-scheduled day

Jayasalini Abramovskikh Moscow, Russia

by Thomas Mcguire

by Thomas Mcguire