Inspiration Letters 18

Creativity Issue: Reflecting on the expressive urge from both mystical and pragmatic points of view...

I enjoy writing, kind of the way I like shoveling snow or getting dental work done. It hurts while I’m doing it, but when it’s over I’m so happy! I think most writers would agree.

Creativity hurts. It’s good that it hurts because it’s supposed to. Being creative hurts because most of the things we create are total garbage and should be thrown away as soon as possible. But I am so happy, that out of the hundreds of poems that I’ve written, that one of them or two of them makes sense and hits real notes.

One of my friends is a bad singer. He formed a group of bad singers and they practiced and practiced Guru’s songs for years and years, singing them badly. After many years, Sri Chinmoy commented that my friend’s singing group had made more progress than all of the other groups because they kept singing and practicing so seriously. The Master really gave a lot of importance on never giving up. When I hear this particular boys’ singing group perform, I am so surprised because they have started singing well.

I remember when the "Florida girls" singing group sang for Guru. Guru was really pleased with their performance, saying that some singers are born and some are made. He said that these singers were made singers, that they have become singers through practice and effort. Through diligence, he remarked, we become poets, or singers or artists or composers.

One of the most creative, wonderful times of my life was when I went on the World Harmony Run in 2005. People might laugh because I didn’t do much writing at all, and I spent most of my time running, cooking hastily for the team or getting much-needed and well-deserved sleep. I remember, however, running through Abiquiu (take THAT evil spell checker!!!) New Mexico, which is where you can find all kinds of strange, enormous and other-worldly rock formations. I remember running in the shadow of a monolithic tower that looked for all the world like the Madonna and Child. I know my imagination helped to carve that image, but I really felt something in that rock. That reminds me of what Michelangelo said, that he doesn’t sculpt anything, he just uncovers what’s already inside the marble, deeply hidden.

Sri Chinmoy said that the very act of running is a gift of dynamism to the world, that when you run, people in different parts of the world can get benefit and inspiration from you. They won’t know who you are, or where this inspiration and energy are coming from, but they can feel it on some level. I like the aphorism that Sri Chinmoy wrote in “The Supreme and His Four Children: Five Spiritual Dictionaries:”

Solitary confinement

Is not meant

For a modern Yogi,

For God wants him

To be a militant Yogi.

Sri Chinmoy is not talking about military force here! Not at all! He’s just saying that the proper role for spiritual Masters and seekers these days is to live bravely in the world, for the betterment and improvement of the world.

While I was running with the World Harmony Run team, I felt that there was a connection between the contemplative life that I strive to lead, and the running, an expression of enthusiasm, hope and joy. That connection is a creativity connection, that urge to manifest something new, higher and brighter on earth. By praying and meditating we get the vision of a higher, ideal life. Through running, swimming and serving the world, according to our capacity and inspiration, we try to make the dream real and to inspire others to join in the world-transformation song and dance. What could be more fulfilling than that?

I remember asking Sri Chinmoy what I should do after graduating college. He told me to go and get a job. He didn’t specify which one, only that it should have a pleasant atmosphere. By acting, by jumping into the unknown world of work (trust me a big leap for a literature nerd from the posh suburbs), he knew I would learn more about myself than by going to graduate school and unraveling the hidden significance of the fires of Dante. By acting, creating and moving, we give ourselves away to the world and we find out who and what we really are.

That reminds me of what Walt Whitman once said:

Behold! I do not give lectures or a little charity;

When I give, I give myself.

Here’s a wonderful talk that Sri Chinmoy gave on creativity in 1998:

I hope this issue, lovingly spun from many creative yarns, may give you joy!

Sincerely,

Mahiruha Klein

Editor

Title artwork: Pavitrata Taylor - see more at Sri Chinmoy Centre Gallery

Creativity is a Pineapple Omelette

Creativity is:

beginning your day with meditation, singing and prayer.

Creativity is:

making a pineapple omelette for breakfast even though you have never heard of such a meal and smiling happily when it turns out to be one of the best omelettes you have ever eaten.

Creativity is:

using a camera to observe the world around you as if you have never seen it before.

Creativity is:

blowing bubbles.

Creativity is:

running in the rain.

Creativity is:

taking the book you have to read for your job under your arm while you go for a walk in nature and sitting on a boulder by the water while you read instead of doing it sitting on a chair in your house.

Creativity is:

planting fragrant flowers that bloom at night.

Creativity is:

cheerful laughter.

Creativity is:

a musical band made up of household objects.

Creativity is:

putting a lawn chair in the front yard and sitting down in the dark to watch a full moon rise in the sky.

Creativity is:

growing vegetables for the first time ever in your own garden – rainbow carrots, Italian peppers, kale, heirloom tomatoes – then looking at them harvested and creating a dish using as many of them as possible without any recipe. Result? a spontaneous vegetarian chili with barbecue sauce, seitan, red kidney beans and carrots, peppers, tomatoes and kale harvested from my garden.

Creativity is:

seeing the sky and its clouds as a storybook.

Creativity is:

the heartbeat of happiness.

Creativity is:

believing I can become another God.

Sharani Robins

Providence, Rhode Island

A Writer’s Life

The life of a writer is a mixture of freedom and fear.

The life of a writer is a mixture of freedom and fear.

Since I left my nine-to-five job, I’ve had an unspoken philosophy that I would never spend too long doing any work I didn’t enjoy. This has given me several moments of bliss, but has also ensured several moments of financial instability to rival anything that Wall Street could provide. Recently, the global recession has made it difficult to write for a living. Magazines, newspapers, everyone is making cutbacks. An ideal opportunity for me to be a starving writer, one of those literary lions whose poverty has somehow been equated with artistic magnitude. (Well, “struggling writer” is perhaps a more accurate term. As long as I know how to make espressos at my local haunt, My Rainbow-Dreams café, I’ll never be starving).

At times, it’s easy to worry about my bank balance. Fortunately, while work is less frequent, it is still coming my way. A feature article for a science magazine. A story for a travel magazine about Australia’s best athletic events. Another travel piece about the wonders of Iceland (which I visited just before overseas trips became a luxury I couldn’t afford). It’s not like I’m writing sonnets or epic novels, but even my current writing assignments are inherently creative, as I try to make science sound colourful or make sporting events sound alluring to the travellers who would rather just laze around at the beach. As I write, even as I research, I enter into another world. I could never do this at my office job, while writing reports or government media releases. It is the process that gives me joy. The pay cheque, whenever it happens, is simply a bonus (but I’ll take it anyway).

Recently, as if to prove that times are tough, I did the unthinkable: I applied for some jobs! I mean, real jobs. They weren’t even writing jobs. But they were jobs for the Australian Broadcasting Corporation, which is starting a new children’s television channel. I love children’s television, and as a few jobs were offered, I applied for a few.

My job applications were works of art. Let’s not judge the quality, but the feeling was certainly there. I put as much effort, as much heart into them as I would put into any book, article or radio play – hoping that, once someone reads them, they could never conceive of hiring anyone else. Then I sent them out (by email, as requested), imagining – as I often do when I send a story to an editor – someone reading them, and being bowled over by the power of my prose.

A few weeks later, I thought that maybe it had worked too well. They were so bowled over that they had never regained consciousness, at least not long enough to reply. I received no email. No message saying “We need you! Come as soon as you can!” Not even a humble (if unfathomable) apology, like “We’re sorry, but we gave the job to someone else.” As I had applied for four jobs, I was truly perplexed.

After sending them a few emails, I was finally told that they hadn’t received any of my applications. Upon further investigation, I discovered that, thanks to an over-vigilant antivirus System, my emails (virus-free, but with the “wrong” files) had never made it – and it was too late. The jobs had been taken. There were no more to come. Thanks to their computers, my career, my future (or at least, possible regular employment) was gone.

But that wasn’t the worst of it. The worst thing was that nobody read my applications. I had spent so much time on them, taken so much care. I don’t know who won these positions, but I’m sure that their applications weren’t nearly as literary as mine. This was not just my ego speaking. At least, I don’t think so. OK, maybe it was. But that wasn’t all that concerned me. Naturally, I had missed the chance of a job. But there was also the fact that I could not share something that, for whatever reason, I had written only to share.

How does a writer handle such crushing news? A few ideas come to mind. Over-indulging on ice-cream. Retreating to your room and watching comedy DVDs. Sitting down for a meditation. I decided that meditation might work best. But not surprisingly, I wasn’t meditating so well.

Instead, I dusted off another writing project. A sitcom. They say that sitcoms are “lowbrow”. But they also say that, if Shakespeare were alive, he’d be writing them. (A different “they”, perhaps.) I disagree with both suggestions. If Shakespeare were alive, he’d be living quite happily on royalties, and wouldn’t need to write anything else. But sitcom writing need not be “lowbrow”. Yes, this is a form worthy of Shakespeare. I’ve tried novels and I’ve tried poetry, and I find them far easier than sitcoms.

A sitcom demands more: as with sonnets or haikus, you must write to a strict format, and you must make people laugh. Not always so easy. It is a challenge, and one that gives me a thrill. Again, I enter another world, where my writing is my entire focus.

Characters I want people to enjoy, to identify with and to like. They come from somewhere within me, I assume, so hopefully a part of me is likeable.

Situations that we can all understand. Perhaps even morals, fables, delivered as cheerfully as possible. Many writings (including many of my writings) are never read by anyone but the writer himself. Now I want to write something that I can share, that can give people joy.

Do you know how challenging that can be? Like a runner trying to surpass his marathon time, a writer throws himself into a new, creative world, hoping to surpass all that he has done. Whatever has happened in his life, whatever dumb things have gone wrong, nothing else matters.

It was some years ago that I realised that I was living three lives – or at least, working in three areas that, on their own, took up enough of my time to be full-time jobs. It was all too much for one person, as I had only so many hours at my disposal.

As my time was limited, something had to go. My first “full-time” position was my spiritual life. The second was my writing. The third was my job, a job that I enjoyed, that served me well and ensured that I was always able to pay the rent. As any sensible person could tell me, it was crucial to me living a secure and comfortable life.

I made my decision almost immediately. The job didn’t stand a chance.

Writing is my dharma, part of my true self. I don’t write because I enjoy it. I write it because, deep within myself, I really have no choice. Faced with such an ultimatum, I should at least try to do as well as I can.

Noivedya Juddery

Canberra, Australia

Making

What pleasure it is to be back at art school! The sculpture studio, like all those rooms so long ago – Nigel’s advanced drawing class, Isao’s water-colour class, Karen’s painting class – is a cross between an alchemist’s laboratory and a shabby potting shed. Around the walls lie discarded student works: the bizarre, the macabre, the simple failures. The smell of plaster of Paris is in the air.

What pleasure it is to be back at art school! The sculpture studio, like all those rooms so long ago – Nigel’s advanced drawing class, Isao’s water-colour class, Karen’s painting class – is a cross between an alchemist’s laboratory and a shabby potting shed. Around the walls lie discarded student works: the bizarre, the macabre, the simple failures. The smell of plaster of Paris is in the air.

For old times’ sake, I make myself a large, black, instant coffee in a large, dirty mug that I find on a shelf.

The Hungry Creek Art School – unlike my own alma mater in the central city, which occupied an ancient brick building infested with the ghosts of long-departed trainee Methodist ministers – is reached at the end of a long and steep gravel road winding into the wild New Zealand native bush. The trees crowd in around the buildings.

The day is grey and wet, and the damp of the bush, of the long-shaded leaf mould, seeps into the studio. We chop some kindling and light a fire in the grate. The tutor powers up her MacBook and soon the flames, the coffee, and Senegalese rock music dispel any gloom. Eventually I take off my woolly hat.

It is a two-day practical workshop on sculpture. The third dimension is something I have long feared but am now just beginning to explore – and explore with increasing enthusiasm.

There are three of us enrolled in the workshop: the Department of Conservation field worker, the accountant, the typesetter. The tutor seems jovial but she fixes us with her steely eyes behind her small glasses with the fire-engine-red frames and tells us that before we start she would like each of us to tell her our “history of making”.

Making? Making. It is not a word I have heard used before. Not our history of artistic achievements – like the beastly men in suits in art galleries want to know before they will speak to you – not our experience of sculpture, not our history of creativity, none of these things. Our ‘history of making’.

She explains that she has young Asian students who have never made anything in their lives. We are New Zealanders and this strikes us as inestimably sad, as a terrible indictment of a bizarre contemporary world lost in some cyber realm divorced from physical reality.

Have we made a batch scones; rattled up a stuffed, fabric camel on the sewing machine; designed a two-storey, wooden mouse cage; constructed a birds’ nesting box and scaled a walnut tree to affix it craftily to a limb (where no bird ever even looked at it); have we heaped up rocks to dam a river; painted a butterfly on a child’s face; climbed a scaffold to paint the house; made a macramé owl? Happily, the answer is yes.

Our ‘history of making’? I made quite a lot of money at my last exhibition but I must cast my mind further back than that.

I remember a fat, newsprint pad that I got for some distant 1970s birthday. When you bent it, the leaves squeaked as they slid against each other. I remember drawing on it, with a blunt, dark pencil, a fearsome bear, a delicate wading bird, a hedgehog wearing a knitted hat.

In school holidays Mum would direct me and my sister in the making of oven cloths out of pieces of hessian, stitching in some intricate manner, now long beyond my recollection, with different coloured wools.

Mum may have encouraged this creativity, but she was herself famously bad at one other creative process: drawing. When she died and was lying in her coffin in the front room, my father, with a great sigh of sadness and loss: “ah Mousey!” he said. ‘Mouse’ was the name he always used of her – a name, strangely, gained from her lack of artistic ability. Sixty odd years before, as a young teacher, she had drawn pictures of mice for her students but had overcome her lack of artistic flair by tracing around coins to form a round body, head, ears, which, with the addition of a few features and a tail, became her signature mouse, the mouse picture that followed her the rest of her life.

This lack of aptitude made, in later years, for games of ‘Pictionary’ that devolved into unrestrained hilarity and hysterical laughter at Mum’s attempts at drawing, for example, a tractor that could be distinguished from a bicycle.

Mum’s creative abilities lay in other fields. In those long nights when she could not sleep she would compose poetry. She could sew any complex garment, knit most things and would, with little provocation, write plays. For my twenty-first birthday she wrote a long, complex play in verse upon an abstruse mythological subject. Not many of my contemporaries could claim such a thing!

Every so often Mum would get up and rip a strip off the wallpaper on some random wall around the house, thus bringing to an end the discussion concerning whether a particular room should be redecorated. After that, all eight of us would clamber into the VW and head off down to the paint and paper shop and pour over sample sheets of wallpaper and charts of paint colours. Everybody had an opinion and everybody expressed that opinion, from the eldest right down to my own pipsqueak views, and eventually – sometimes after several visits – the wretched salesman was able to make a sale. Then it was weeks of stripping and scraping and sanding and knocking out cupboards or smashing down ceilings and painting and paper hanging and new tiles and lino and cornices and then discussions about whether the carpet should be replaced or removed and if a natural, brown, sheepskin rug was sufficiently cool in the late ’70s.

My ‘history of making’ began in an environment where ‘making’ was natural and inevitable.

I recall the rich smell of my father’s oil paints; and the endless stomp, stomp, stomp from the upstairs room where he practised his violin – beating time with his foot heavily on the floor; and his motorbike engine disassembled and spread out in the shed.

My siblings? Michael, when not writing some academic treatise on German literature, was painstakingly constructing a huge and detailed miniature landscape through which model trains moved almost as an afterthought; Kathleen would be playing Don McLean songs on her guitar or creating some precise masterwork of the gardener’s art in the front yard; how many intricate jerseys did Maureen knit for me and who was it that described her singing voice as bell-like?; Nicholas drew the large, lifelike pencil drawing of the Emperor of Ethiopia that had pride of place on my bedroom wall, and in the early mornings as I lay in bed reading – heaven only knows why – ‘Young Heroes of the Soviet Merchant Marine’ before school, he would be in the next room practising some complex Shostakovich violin concerto; every afternoon Stephanie was practising her flute and the piano.

Music, music, everywhere – somebody always off to practise or perform with the Harmonic Society or the Cathedral Choir or St Mary’s Choir or the Orchestral Society or the Teachers’ College Choir or the School Choir or the Inter-school Choir or the Harmonic Children or the Schola or the Cecilian Singers or the City Choir or the Southern Consort of Voices or the Mairehau High School Orchestra or the Viennese Orchestra or… heaven knows what else, and the rest of the time we were all locked in the front room practising elaborate four-part settings of the Latin Mass from the late sixteenth century.

There were only two topics of conversation in the McBryde family: music and God. What a sad day it was when I became a national-champion runner!

By lunchtime on the first day of our sculpture workshop the sun has come out. We share our food at an outside table and discuss the work of French sculptor Louise Bourgeois and the status on off-shore islands of the Polynesian kiore rat. It emerges in conversation that none of us has a television. Is it possible that this is not significant?

It seems to me that all ‘making’ – from wallpaper hanging to William Byrd’s 1590s Four-Part Mass to the most exquisite of visual fine arts – may well spring from the same source.

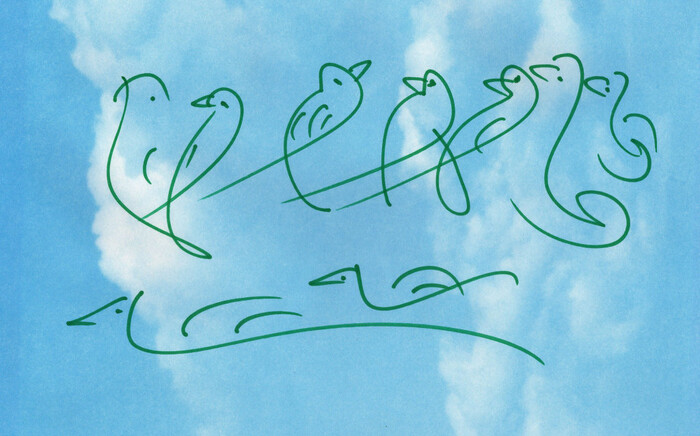

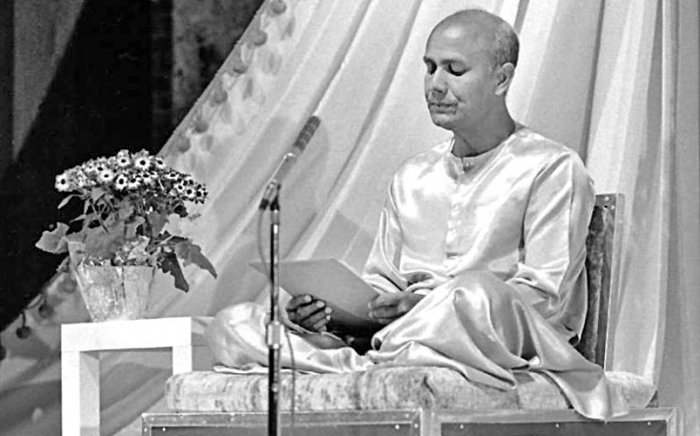

Sri Chinmoy referred to his own art as ‘Jharna Kala’ – ‘fountain art’ – art springing spontaneously from the source. It is a beautiful expression, so evocative of the welling up of inspiration from some profound depths, a boundless upward thrust of life-giving water from the primordial springs of the soul, a ceaseless and joyous play of water in sunlit delight.

While the phrase was his own, and perhaps nobody better exemplified this fountain flow than he, I never thought it a unique view of creativity, for this surely is the experience of many artists and creative practitioners in various realms.

Ideas and forms and expressions simply flow upwards into us and it is our job, as much as possible, to get out of their way, to act as faithfully as possible as servants of their expression without imposing on them the lumbering constraints of our minds and techniques.

Sri Chinmoy no doubt looked with clear eyes into the depths and saw plainly the source from which art springs. Those of us who do not see the distant hatching grounds of creation can still delight to catch its winged flocks on their migrations, feel joy to let its waters flow through us.

It was, I believe, Dr. Betty Edwards in her book Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain – a book without which the entire course of my own life would have taken a very different path from that which it has – who pointed out the strange fact that there is no way to control this fountain-like flow of creativity, no way to turn it on or off by an act of will, but there is a way of luring it closer to us, a way of encouraging it, and that is the actual physical act of creation. It is when we lose ourselves in the actual process of applying the paint, of guiding the pencil across the paper, making the light and dark marks upon the paper, that our creativity begins to flow. It is in the execution that the ideas arise.

The whole process then becomes akin to meditation – an abandonment of ourselves. Often when painting I have found myself – a particular vacant, slack-jawed expression on my face – time forgotten, feeling myself to be more a conduit than an actual active participant.

A few days after the workshop, the tutor sends me an email with some photographs attached which she had taken of the strange pieces I had constructed under her tutelage – the latest additions to my ‘history of making’. “A pleasure to have you in the workshop and I hope you continue with your intuitive and thoughtful making,” she writes.

Barney McBryde

Auckland, New Zealand

Creativity

by Tom McGuire

We ourselves are creations, for we owe our existence to a higher source. This same source continues to create in and through us. This, I believe, is the basis for a spiritual approach to creativity.

In our modern world we seem to be more concerned with what someone has accomplished than who they really are. The veneration once given to sages who meditated in the high mountains has been replaced by our bedazzlement with movie stars and politicians, weavers of words and lords of imagery. It is in this context that Sri Chinmoy arrived on the scene, becoming perhaps the most voluminous spiritual artist of all time.

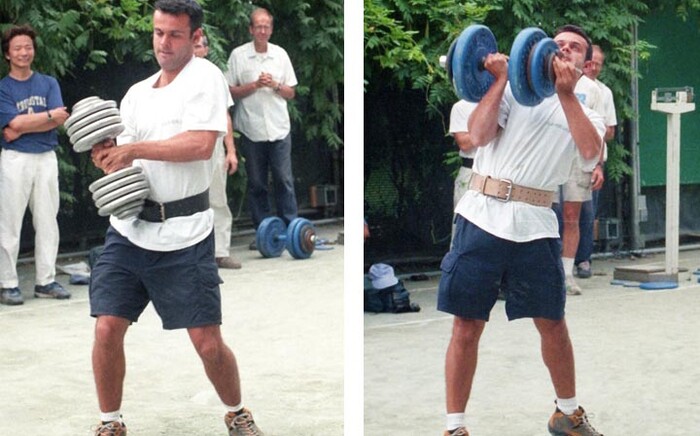

Sri Chinmoy was the abundant expression of what for most human beings is only hidden potential. He took upon himself the vast tapestry of human expression and made each field uniquely his own. In his hands the pen became a mighty sword of mental illumination; the paintbrush a magic wand revealing portals into the Beyond for all to see; the musical instrument a beacon calling all truth-seekers to play their part in the universal symphony, and tonnes of lifted metal were a symbol of all inert matter that must ascend by the spirit’s touch.

One of the most profound things I have learned from Sri Chinmoy is that we are most creative when we let a higher power act in and through us. When asked about his method of painting or composing, with supreme humility Sri Chinmoy would say that he was only an instrument of the Divine.

Significantly, Sri Chinmoy tells us that “the supreme Art is to know the Supreme Artist intimately, within and without” a knowledge which “cannot but guide all our movements on artistic lines.” It is a beautiful thought that the same creative power that summoned us into being, and intricately fashioned every hair and cell, continues to act with the same intensity in our every thought and deed. The more we allow this power to unfold within us the more remarkable we can become in our lives and our accomplishments.

Tom McGuire

Auckland, New Zealand

Photograph by Sharani

Make Your Writing Effortless

7 ideas to make your writing effortless

Writing doesn’t have to be hard; in fact it can be as easy and natural as spoken conversation. All writers struggle in the beginning to develop creativity and flow; use the following seven tips to sharpen your talent and reach your goals.

1. Carry a notebook

Carry a notebook with you at all times; when inspiration hits, seize it and your notebook with both hands. All writers recommend carrying a notebook; use it for the surreptitious jotting of thoughts when and where ever they might appear. Jack Kerouac, foremost writer of the Beat movement of the 50’s and ’60s—a moniker and eminence he was deeply uncomfortable with—carried one everywhere, forever sketching poetry and novels to be in the most unlikely of places—”Scribbled secret notebooks, and wild typewritten pages, for yr own joy” in his words.

Likewise Walt Whitman, 19th Century ‘Father of American Poetry’ and inspiration to Kerouac, who went one step further and carried an entire manuscript, a paperweight sized bundle that would one day be his Leaves of Grass.

2. But use it in the right place

Funnily enough, this oft revised and reworked masterpiece was the cause of Whitman’s dismissal from at least one job—fired from the Department of the Interior by an enraged employer upon closer inspection of the ‘paperwork’ on his desk. Which suggests that some places are better to write in than others, although in Whitman’s defence, most writers can relate to the truth that inspiration may strike in the most unexpected places.

3. Make writing a good habit

Writing is a good habit which can benefit from a little encouragement. To this ends, many writers recommend a specific place to write, almost like a meditation shrine, dedicated to this solo, inspirational practise. For some a specific time of day is conducive—a daily regimen just like eating, sleeping and exercise. Creativity can wax and wane like the passage of the moon; take time and place of writing as two aids to assist obstructing clouds to part.

4. Regularity builds the muscles of writing

Make an attempt to write every day, without thought or judgment for the quality you produce. Writing is like a creative flow; it will not begin if you do not turn on the tap. One method is to write like a river bursting its dam, words spilling over onto the paper before you. Follow the rivers’ flow as far as you can, and in time the distance you travel will grow. Look not at this metaphorical river’s banks or rocks ahead of you; flow forth like water, always moving.

5. Writing is like meditation

Writing can be like the act of meditation itself, a secret known to centuries of haiku poets who were also meditators, and practised it as such. Write regularly, in silence and with one-pointed focus to achieve your goal. Furthermore, the discipline of regular practise, as in meditation, encourages an ever deepening flow of creativity, and a more fruitful, productive experience.

6. Suspend critical thought

Suspend judgment during a first draft, even if your mind screams that you are writing poorly. More important is to write, write, write; regardless of quality let the words pour upon the page—revising and polishing are for a later date. The editing process is a different mindset from that of writing, which requires creativity to flow directed but unimpeded; for the sake of creativity leave this more critical part of your being to one side. It is not without reason that professional writing seldom sees the occupations of writer and editor in a single person.

7. Exercise your body, not your mind

Running, and exercise in general, will actually help your writing. Meditation teacher Sri Chinmoy calls running meditation for the body; it clears the mind and purifies the emotions in the manner of a breath of fresh air, dispersing anger and depression as though clouds in the sky. Negative qualities are an anathema to creativity—it’s total polar opposite; take physical exercise as a simple tool to clear the road ahead when you are writing. It also makes a good time out.

Writing is like running in a sense; the hardest part is getting under way, but once started a momentum is built which will carry you along. Surrender to this and your writing may one day become effortless.

Jaitra Gillespie

Auckland, New Zealand

Creativity Where You Least Expect It

In the creative thinking process the mind can experience concepts or thoughts that are uplifting, inspiring, or plainly unexpected. The experience of creativity could be manifested in activities where one may least expect it.

Let us think of the common experience of procrastination. I found myself procrastinating quite a bit in starting to write this article until I realized how creative I was being by creating excuses to procrastinate. There always seemed to be something more important to do to fill the time I would have taken to write this. Although I knew about this opportunity for some weeks now as the deadline was moved ahead quite a bit, I creatively kept inching towards the new deadline with procrastination while in my heart I really wanted to write something.

Perhaps my mind did not feel creative enough to sit down and get my fingers to type anything meaningful. That in itself was a creative act of procrastination that I finally decided to express here. We have all heard of, or have had creative excuses to procrastinate or even avoid responsibilities in many walks of life. Finding ways to skip school, work or other daily routines that may not always be the most fun or fulfilling, can be a very creative exercise. We all have heard the once creative excuse for the student who did not do his homework: “The dog ate my homework”. This now trite excuse I am sure has been expanded upon and modernized in ways like:”My hard drive crashed” or “My laser printer ran out of toner.”

Other unexpected manifestations of creativity can be seen in exercise although it may sometimes look or even feel boring. When running in a long distance race for instance, one must think of ways to keep the energy high and the inspiration level strong enough to endure the tiredness and possible pain and other problems that may arise. We have all heard of creative problem solving in other walks of life. In a long race one may have to react quickly and convincingly in creative ways as they encounter situations and problems that may try to stop their progress at every moment.

One example from an experience I had many years ago was when I was trying to run a 31 mile training run for my 31st birthday. It was late at night and I was not feeling that well. I decided to ride my bicycle 31 miles instead so as to get it over with more quickly and go to bed so I can get up and go to work in the morning. I felt this was a creative way to get around the 31 miles of running although in my heart I really wanted to run the miles for my birthday which was becoming a tradition with me at the time.

After a two hour bike ride I felt like I should run at least a few laps of the 3 mile loop I was on. I tried to find ways to convince myself to run the 31 miles anyway without trying to rationalize all the obvious reasons why I should not do it. It was 3:00 in the morning by then, I had a cold, I had to work in the morning, I already rode 31 miles and I was a bit tired. All this made sense to me but still in my heart I wanted to run the 31 miles. I had to start some creative problem solving quickly before surrendering to logic and rational thinking.

I decided to try and utilize some of the things I learned from meditation through the years to that point. If I could rid my mind of thoughts perhaps I could experience more inspiration and energy that would keep me going for another few hours. Since creative energy and creativity come from the Creator then I would try to tap in on some of that creative inspiration as I ran. So I looked at the dark sky where I observed the moon and the stars. Through rhythmical breathing and conscious focusing I tried to get rid of all thoughts about time and just identify with the infinite space which we are part of. As I silently tried to experience the spectacle of the vast sky and infinite Universe in which we live, my quiet mind did not resist and instead some creative thoughts starting coming to me.

I realized that as I looked upon the moon that it was also doing ‘laps’ around the earth and it has been doing this for billions of years. The earth we are on is also going around and around in circles for billions of years without stopping or hesitation. Everything is spinning with it, even the microscopic electrons in the atoms, etc. We are not separate from all this. We are part of this whole amazing spinning system, larger than the largest and smaller than the smallest. So instead of separating myself from it with my mind I tried to feel the creative energy which was being produced around me at every second. As I circled the course over and over I realized that this creative energy which was not being blocked by limited mind anymore was giving me the strength and joy to complete the 31 miles that in my heart I wanted to do originally.

This form of creativity which may not have a tangible manifestation nevertheless was an obvious experience of creative energy that allowed me to do something my mind was resisting, thus allowing me to solve this dilemma in ways unexpected. In the creative arts of writing, painting, music, etc. one may get mental blocks that do not allow the creative energy to flow freely. If one can surrender the thoughts and limiting mind to higher realities through concentration and meditation then creativity is bound to flow more freely.

We see then that creativity can be manifested in the creative arts as well as in other unexpected walks of life as long as the source of creativity is tapped in some form or another. According to Sri Chinmoy, who himself tapped into and manifested an enormous amount of creativity in every field of endeavor he undertook his whole life,

“Creativity does not mean that one has to write poems or articles, or compose songs. Creativity means one's inner concern for the expansion of what he is or what he has. When one consciously wants to go beyond his capacity and beyond his achievement, only then do we find real creativity, only then can creativity have its proper value, worth and purpose.”

-Sri Chinmoy, from Illumination-Fruits

With this very meaningful statement in mind, let us all go about life invoking the creative spirit which springs from the source of creativity and can feed us at every moment. Again in the words of Sri Chinmoy,

“Where does one find the source of creativity? If one wants his creation to be permanent and eternal, then that creation must come from the soul—not from the mind, not from the vital, not even from the heart. In the heart, in the mind, in the vital and even in the gross physical, one can also see creativity, but the achievements of that creativity can never be lasting. It is only the soul's creativity that can be abiding.”

-Sri Chinmoy, from Illumination-Fruits

Arpan DeAngelo

New York, USA

Photograph by Arpan

Beethoven and Spelling Bees

I wanted to write an article about my favorite math teacher , the one who opened my eyes to the unique wonder and beauty of mathematics, who showed me that numbers and equations can be as interesting and as fun as creative writing and poetry. But I never had that kind of math teacher. I always hated it. Maybe if I had been good at math, I would have fond memories of my dear algebra and calculus teachers, smiling approvingly at me as I solved yet another differential equation, whatever that is. But instead, I remember these old teachers scowling at me as I explained to them why I didn’t do my homework. It always boiled down to “I didn’t want to.”

I wanted to write an article about my favorite math teacher , the one who opened my eyes to the unique wonder and beauty of mathematics, who showed me that numbers and equations can be as interesting and as fun as creative writing and poetry. But I never had that kind of math teacher. I always hated it. Maybe if I had been good at math, I would have fond memories of my dear algebra and calculus teachers, smiling approvingly at me as I solved yet another differential equation, whatever that is. But instead, I remember these old teachers scowling at me as I explained to them why I didn’t do my homework. It always boiled down to “I didn’t want to.”

Fortunately, I went to school *after* corporal punishment had been banned. Given the looks some of those teachers gave me, I’m sure they would have thrown a few erasers at me, had they not faced the likelihood of prison time for it.

But here I am, a guy in his mid-thirties, and I don’t remember how to long divide. No matter! That’s what calculators are for.

I can spell pretty good, most of the time. That’s because I love English, I love the eccentricities and foibles of my mother tongue. One of my favorite examples are the homophones “kernel” and “colonel”. They’re pronounced the same way, even though they mean totally different things. A “kernel” is the seed or the husk in the middle of a grain or a nut, I think. While a “colonel” is a military officer. Now look at the two words side by side. Do you see anything unusual? Yes! That’s it! There’s no ‘r’ in colonel! So, why is it pronounced like ‘kernel’?

Webster’s has the answer- apparently, at one time, the English language had two words for that military rank- colonel and coronel- the first from the Italian and the second from the French. We kept the Italian spelling and the French pronunciation, God knows why.

Another word I like is “enjoin”. It means two things- “to order someone to do something” and also “to forbid someone from doing something”.

Now, maybe it’s just me- but isn’t it a mathematical rule that if you take a positive and a negative which both have the same value, and you put them together, they will cancel each other out? So, why do we still have the word “enjoin” if it has two meanings which directly contradict each other? I mean, if someone enjoined me to go take out the trash, I wouldn’t know what to do!

I admire people who make a living doing creative work. I’m too attached to my three square meals and roof to jump into the unknown vortex of freelance writing. But I admire those who do. They are true state-smashers, anarchists who rise above the fray by pointing to the rainbows and stars beyond the tumult and babble of the mundane. Ooh…I’m waxing eloquent today! Like many creative folks, I’ve chosen a simple, menial job that gives me ample time to think and write. Sometimes, having a job, however humble, can keep you stationed on planet earth.

I have a large record collection, hundreds of 331/2s from the fifties to the early eighties. I’m sure many of the records that I love have passed through many hands, have been listened to, admired and enjoyed by many people. And I can feel it. I have the late string quartets of Beethoven, as interpreted by the Budapest String Quartet, on the Columbia label. Apparently, a wealthy heiress gifted four priceless Stradivari to the National Gallery in Washington. Stringed instruments decay if nobody plays upon them, so the Gallery arranged for the world-famous Budapest ensemble to record the complete Beethoven string quartet cycle using these precious instruments.

One of the most beautiful quartets in the later series is opus 132 in A minor (number 15). Beethoven termed the slow, haunting middle movement "Heiliger Dankgesang eines Genesenen an die Gottheit, in der lydischen Tonart" (Holy Song of Thanksgiving by a Convalescent to the Divinity, in the Lydian Mode).

He had been suffering from a serious sickness, from which he thought he might not recover. Upon getting his health back, he penned this quartet, with that strange, slow movement that sounds like it comes from another planet. There’s really nothing like it, and I can’t describe it, but may only suggest that the reader listen to it.

When I come to that movement on my record, I hear many more hisses, pops and rasping than usual. Apparently, whoever owed this record before me, really loved that movement. And somehow, I can feel that person’s love and devotion to this music. It’s all there.

This reminds me of something Sri Chinmoy once wrote. I am sorry I cannot find the original quote. But a seeker once asked him if there is any benefit to listening to the part of a tape of one of the Master’s meditations where he is not speaking. And Sri Chinmoy responded by saying that his silence is very, very powerful and that everything is recorded there.

I’m going to conclude with a very significant answer that Sri Chinmoy gave on the creative life. You can find it here. I don’t want to excerpt it, as I feel his comments are beautiful and important and should be read in their entirety.

With much love to my ever-blossoming, heart-creating and dream-manifesting family,

Mahiruha Klein

Chicago, USA

Photograph/Artwork: Ed Silverton

Down by the River: Remembering My Grandfather

In a brief end of life memoir called Songs of the River – aptly named, for he was buried in a tiny rural graveyard overlooking the silt-brown flood of the Taierei – my grandfather left a few belated snapshots of his life that later became a source of much fascination to his kin in another age. His thoughtful and wandering prose flowed across the yellowing pages of his narratives in a fluid, archaic hand, smooth as water and beautiful, unrelentingly truthful with the kind of candor normally reserved for one’s diary.

The Olivetti typewriter my mother used to transcribe his introspections into legible print did a huge disservice to his spirited and rich handwriting, reducing the lovely flourishes of his pen to a featureless and barren uniformity. The original embodied his very blood, breath and heartbeat—the loops and swirls of his labor swooped and soared, capturing the crests and troughs of his life, distilled into ink the retrospections of his probing memory, the soothing water songs of the Taierei river. From the pages owls called from the dark folds of forest, the thoughts of his later solitude rose up and lodged in our hearts, everything of him there in the dance of ink that was his last summation.

In the room adjacent to my childhood’s unfolding my mother clacked dutifully away, the blows of the mechanical Olivetti like the chatter of small arms fire from grandfather’s war years, a rat-a-tat fusillade as she flew across familiar keys then a long pause before the single shot of an elusive, hard to find letter. A careless reader had spilled tea onto the original parchment but this somehow elevated it’s status, imparted an air of historicity, a stained manuscript retrieved from antiquity.

“Where does a man begin and end, what are his boundaries” he writes, “since what I call myself extends beyond the reach of scrawny arms, of flesh. Knowing surpasses knowledge, sensibility outlasts thought, life outreaches living, self soars beyond mortality. Each day I am less and less a man and more of spirit. How glad I shall be to awaken from this dream of life and to return to something hidden so long from understanding, sensed all around. For two days and nights the patient Taierei has been whispering it’s secrets to me—but yet I cannot properly understand…”

What did he mean? We children brooded over the freshly typed pages in fascination, or traced with our fingers the wild calligraphy that urged understanding through feeling, not language. The manuscript of his self-revelations was alive—to touch it was to connect across time, to grasp the hard calloused hands and be guided by them across the paddocks on the river flats to the water’s edge, sit with him in listening.

“Ssshhhh…” said mother, “Close your eyes and listen”. We waited avidly, retracing his footsteps and the generous sharing of his thoughts. “I must become as mute as the stones, purposeless as wind, yielding as water. I had all along thought that only I existed, that landscape, tree, earth and sky existed only in me. But now I have come to see that I am only a part of this. I am joined with the river stones, I am the wind in the forest, my spirit fills the folded hills.”

After his death—he was found stretched out peacefully on the harsh grey blankets of a cottage bed, a cow grazing outside the door to his whare – the local Maori cremated him in a nearby field, wrapping his head in wet sacking to preserve the skull. The later headstone satisfied the civic authorities as to his death, but in reality the ground beneath the simple epitaph did not contain his remains – following the local customs these were scattered into the landscape. Pages of his journal litter the wooden planks of the floor, the words spiraling up into my thoughts in later years of reading.

“Today the Maori dispatched a boar down by the river. Slaughtered more likely. Squeals of terror, pig screams. The dogs cringe in the yellow grass, tails tucked in, fawning. Why do we prey on all other species, methodical beasts of prey? Separate, devoid of pity. The river bloodied with its death, a cloud of pink milk drifting downstream. The severed head sits in the long grass, pink tongued, eyes open, still bright and unclouded when I wander down, watchful and calm now, almost reminiscent—should have known, all those turnips, groomed for this. Those long pale eyelashes. Pretty pretty. Offal pegged out on a makeshift clothesline like strips of bloodied rags. Use everything. Across the river the dark forest looms, sphinx-like, indifferent as the river stones, seen all this since eternity began, life cheap as flies. Sadness rolls in like a cloudbank. Scratched his back with my hard knuckles just a week ago while he grunted with pleasure, trusting me. Such cruelty. Beasts of prey.”

I was introduced to the skull of my grandfather at the age of fifteen on a rare trip to Dunedin, the last of him thrust into my hands in a chill and silent room where only an ancient clock chronicled the passage of time present, time past. Bequeathed a single yellowed boar’s tusk and a great silver pocket watch, long chain, antlered stags locked in combat embossed on the frontspiece. A hint of charring on the white skull reminded of the macabre fashion of his disposal and I brooded over this relic with much interest. The force of his life was still here, this thing in my hands was my ancestor. In those moments alone, and through some osmosis of kinship, he imparted that day a sense of mystery and of some unspoken continuity between us, and some part of me turned away from what I had come to expect of my life to choose another way. He had simply passed the baton, and I had gladly taken it.

William Benjamin Dallas. Your skull, sir. Charred a little. The gaping eye sockets, smooth forehead with those zig-zag sutures of melded bone, the promontories of jutting brow, an orator, fearless in your questing. Reflesh the empty jaw, tongued, eyed, what were you like, enigma of it all. Whisper your words while staring at you, familiar words of my own puzzlement and questing. Living words, not like this empty gourd, a Halloween mask, husk of bone. Oh, my first intimations of mortality. Though I don’t believe in death, not even yours grandfather Dallas, though I peer at your burned relics for answers, stare into your hollows like a crystal ball.

I have promised myself sentimentally to revisit the river flats where he wrote and died, and to pen a few lines of my own there, not in memoriam but also in questing, to take what he might have discovered a little further if some grace of insight is given. But I know what I will find, for I have also spent summers and solitary winters in remote places, lain awake at night, heard the river songs purring at the edge of sleep, seen the stars slowly turn across the universe through the skylight window.

“I dream you into being” wrote grandfather of everything around him, “and you become real even to me. But I am not real to myself, and know you for what you are.”

If time, space, self and other are all constructs of our imagining and have no existence beyond our own dreaming, then one day I do hope to pass through the painted veil, recapture the old man, take him by the hand across the fields to the Taierei, watch the bellbirds playing up in the kowhai trees and talk awhile. We’ll swap notes about the great mystery of it all, at night watch the universe turning. I’ll recite some of my favorite poems to a kindred spirit, simple things that I know he will like, all of this while perhaps knowing that everything that is, is contained within me, and the words on the pages of his diary and the death of the boar, the night songs of the river and the conundrum of stars are only my own dreaming and it is only myself that remains to be found.

"We shall not cease from exploration

And the end of all our exploring

Will be to arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time."

-T.S.Eliot, from Four Quartets

Jogyata Dallas

Auckland, New Zealand

Our members

Stories

First-hand experiences of meditation and spirituality.

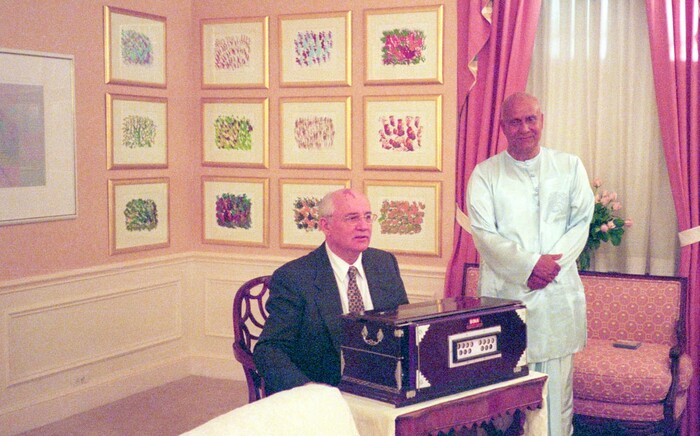

President Gorbachev: a special soul brought down for a special reason

Mridanga Spencer Ipswich, United Kingdom

The first time that I really understood that I had a soul

Jogyata Dallas Auckland, New Zealand

Sri Chinmoy performs on the world's largest organ

Prachar Stegemann Canberra, Australia

Akuti: a pioneer-jewel in our Centre

Akuti Eisamann Connecticut, United States

My life with Sri Chinmoy

Namrata Moses New York, United States

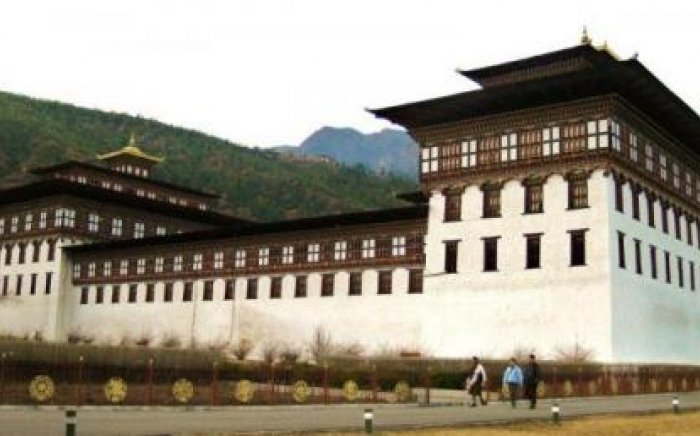

Bhutan, A Country Less Travelled...

Ambarish Keenan Dublin, Ireland

I just knew from the moment I saw him

Ashrita Furman New York, United States

Soul-Birds take flight

Jogyata Dallas Auckland, New Zealand

A Quest for Happiness

Abhinabha Tangerman Amsterdam, Netherlands

Praying for God’s Grace to Descend

Sweta Pradhan Kathmandu, Nepal

The day I made a useless and ridiculous weightlifting machine for Guru

Devashishu Torpy London, United Kingdom

Meeting Sri Chinmoy for the first time

Janaka Spence Edinburgh, United Kingdom

Failures are the pillars of success

Anugata Bach New York, United StatesSuggested videos

interviews with Sri Chinmoy's students

What drew me to Sri Chinmoy's path

Nikolaus Drekonja San Diego, United States

My first experience with Sri Chinmoy

Nayak Polissar Seattle, United States

Running a Six-Day Race

Ratuja Zub Minsk, Belarus

What is it like on the Peace Run?

Nikolaus Drekonja San Diego, United States

Beginnings of a spiritual journey

Mahatapa Palit New York, United States

When I met Sri Chinmoy for the first time

Baridhi Yonchev Sofia, Bulgaria

2 things that surprised me about the spiritual life

Jayasalini Abramovskikh Moscow, Russia

Except where explicitly stated otherwise, the contents of this site are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. read more »

SriChinmoyCentre.org is a Vasudeva Server project.