Inspiration-Letters 11

Sacred Space Edition

Sacred Space Edition

Dear Reader,

I suppose I should put “vacuum my goshdarned room” in my appointment calendar, because whenever I vacuum the faded carpet, and pick up the socks that have lain there since before the Monroe Doctrine and confess that I’m really never going to listen to my extensive collection of Neil Diamond tapes ever again and that it’s perfectly OK to throw them out or exchange them for baseball cards, I really do feel lighter, happier and more free.

I suppose I should put “vacuum my goshdarned room” in my appointment calendar, because whenever I vacuum the faded carpet, and pick up the socks that have lain there since before the Monroe Doctrine and confess that I’m really never going to listen to my extensive collection of Neil Diamond tapes ever again and that it’s perfectly OK to throw them out or exchange them for baseball cards, I really do feel lighter, happier and more free.

Clutter! Yes, fellow clutterholics, we collect just for the sake of it, we buy an old book and think we shall read it and weep with joy in the coming years that we were wise enough to buy it, but then we forget it and it sits there forever with all the other things we bought but never really wanted or needed.

I bought a good book about clearing out clutter and making our personal spaces safe and sacred. I’ve found that it’s good to throw things out a little bit at a time. That way there’s no regret. Many years ago, I acquired this twelve tome series on the flora and fauna of Queens, New York, which I’ve never even looked at, and each week I throw out one volume (did you know Queens used to have kangaroos in prehistoric times? Well, it didn’t but I’m sure these books must contain some shocking revelations that I would’ve discovered had I ever gotten up the pluck to read them).

When I look at my apartment, really look at it, I am surprised at how much stuff I own that I do not love or want. I bought these really cheap garment racks and bookshelves from Ikea that I now absolutely detest. At the same time, my neighbor gave me his grandmother’s old writing desk and I love it. It’s made of good solid wood, and it’s endowed with pleasing curves instead of the harsh edges of most modern furniture.

When my mother died, I would sometimes go into her closet when nobody else was around and just stand there in the darkness, feeling her clothes against me. It meant so much to me that we still had something of hers left.

The only thing I have left of her these days is a portrait, taken of her when she was just a little girl. It’s almost an impressionistic work—my mother stands looking at the viewer with big, sad eyes and just a hint of a half-smile. The background is a wash of gentle greens and faint blues blending together almost like a body of water. The eyes absolutely sparkle with life.

I’ve kept it in storage for many years, with my records. Recently, I got a turntable and I brushed off my records and I also took out the painting of my mom and hung it on the wall. I put a vase of flowers in front of it, making a makeshift shrine to her.

I’m not sure if I will keep the painting, because her passing was so painful for me, and it’s not really a happy portrait. There’s a lot of mature sadness in her girlish little face. I guess I just have to learn how to let go.

And maybe that’s what sacred space means after all—letting go. In a truly holy place, we heave a sigh of relief that sacred space still exists in this world, that we can access a kind of joy that no loss or death can ever tarnish.

I wish all of my fellow hoarders and burrowing bibliophiles lots of luck in clearing out their long-cherished collections, to let some beams of fresh morning light into their hobbit holes.

Mahiruha of Shopping Bag-EndEditor

Title photograph: Pavitrata Taylor

Landing in New York City after an almost thirteen hour nonstop flight from Tokyo, I breathe a sigh of relief. Luggage finally claimed and passport stamped for my return to America, I feel that the journey is almost over. Ah yes, don't forget customs—that form filled out on the plane where I struggled to guess how much I spent on souvenirs and gifts out of the yen bought at the Tokyo airport the day I arrived. I hand the customs officer my form and he passes me through—nothing to declare. Well—nothing except the evidence of a weakness for "Hello Kitty" dressed in kimonos on a variety of items!

Now a week has passed. Feeling infinitely more normal than a week ago Monday (that being my first day back to work), I'm alive and alert enough to appreciate that a beautiful summer day is enjoyably in progress. The weather is nothing less than perfect—83F/28C, low humidity and a positively angelic breeze lightly blowing. Arriving home from work, I decide to wait until closer to sunset before I take a stroll on the bike path near my house.

With my camera tucked inside a waist pack, I walk along feeling so contented. Our spring and summer has been especially rainy so a simple summer breeze and sunset offer themselves as an unparalleled gift. Soon I'm chasing after a large monarch butterfly because it reminds me of Japan. Japan was teeming with butterflies and this association between the two still resonates. The butterfly fluttered away out of sight without me catching a photo of it.

I turn around and my attention is divided between the sun almost setting on the right horizon and the flock of swans up ahead in the cove on the left. Taking inventory, I count about 15 or 16 swans all grouped near a little outcropping of rock close to the path.

I cut off the path and up to the bank's edge, taking occasional steps back to watch the setting sun. I am feeling so completely peaceful and content because of the glorious weather. I cannot help but imagine that the swans have the same sentiment. They look more languid than usual and a number of them are using their body as a downy pillow for their head. Perhaps ever guilty of anthropomorphism, I'm utterly convinced that they are enjoying this beautiful summer evening sunset just as much as myself.

Memories tug at my awareness as I take photos of the swans as the sun is setting. My first toe in the water with photography a little over a year ago started with a fascination for photos of swans at the bike path—particularly at sunset! Now a year+ later, I delight in trying to capture their languid movements, the pink dreamy sunset tint of my surroundings and relish the fun of taking photos of them through the tall fronds of grass on the cove bank. I bask in the satisfaction of tangible progress in my swan/sunset picture-taking abilities.

Then the sun actually sets and the sky becomes a wash of pink, orange, grey, clouds and blue background sky. The colours march into the night's darkness. I watch a different kind of beginning deep inside this day's ending as the pink and orange hues descend onto the water, the swans and into my heart,

Although Mother Nature sings us a dreamy lullaby of sunset, I suddenly get rather excited! It's here! I feel it! The same peace from Japan - I still taste it and sense it all around me out on this path even though it is busy with wayfarers and despite the Providence city skyline etched by the sunset up ahead. I've been home a week back in my regular routine and now that the jet lag fog disperses the peace is still here. Hallelujah! If it could be measured in density in the air, say a part per million, it isn't as strong as Japan's inner silence but I know for certain that it would register if measured.

The sense of silence's constant renewal which I felt in Japan isn't the same, but I am thrilled that it is still lodged inside me. Nothing to declare? How false is that? I need to find that customs form and check off the box marked "other" so that I can more accurately portray what I carried home from Japan. I suppose the customs form doesn't have a section for beauty, inner peace and tranquility but I know that I have exported all of them back to America as clearly as my Hello Kitty souvenirs. I know it because I have never felt such deep contentment and peace out on the Bike Path as on this swan sunset evening.

When I look at the photos from that night added to my gallery album, it still reverberates. I do not know if it will for you as well, but a swan dressed in pink sunset colours is a pretty sight just the same. The symmetry of the two swans in 'Sunset Swans Snooze' makes them seem like twins. They looked like they were feeling just as lazy dazy as me on a summer's eve.

Now I know one doesn't have to travel to Japan to find inner silence and peace since the simple act of meditation draws from the same well. Nonetheless, Japan offered this peace thirsty traveller a blessingful dose. I will have to fill out that form all over again since after all I have ever so much to declare. Thank you, Japan. Thank you so much.

Sharani Robins

Rhode Island, USA

Photograph: Sharani Robins

Only an hour, the schedule says. Okay, perhaps an hour and ten minutes. The schedule is largely in my head, so I can flex it a little if needs be. Yesterday was two hours, so today should be for recovery mostly. Pace checked, moderate, perhaps slow.

Slow? No way, I’m flying! What is it about running that the more miles you grind out, the lighter it becomes? A physiological paradox. I should be tired from yesterday or at least a bit stiff, but my body glides like a hovercraft over a smooth sea of asphalt and my legs feel they’re made out of elastic. It’s raining torrents. I couldn’t care less.

I’ve been running for as long as I can remember. From the moment I learned how to walk, I also learnt how to run. In my father’s apartment stands a picture of me where I am running on the beach, two or three years old. As a little kid I played soccer every day, up until my adolescent years. Always running, be it usually after a ball. In soccer running is more of a by-product, a necessary evil to get towards or away from the ball. When I turned sixteen however soccer had lost much of its charm. Being short and fragile for my age, I felt oddly out of place and quite intimidated on the soccer pitch amidst my peers who seemed to grow like mushrooms, turning into half-giants before my very eyes. Hormones started kicking in, at least for them, while my own still largely ignored me. With every duel for the ball I felt like a David wrestling Goliath. Everything became very physical and most of the fun was gone. So I registered with a local running club and ran twice a week, just for the sake of running. Although I had some talent, it was boring. There was no play involved, no excitement, no fun. It was monotonous. At sixteen the finer subtleties of running were still a heaven too far for me. My one year running career ended with the famous 15K ‘Seven Hills Race’ in my home town of Nijmegen, which I finished in just over an hour. It wasn’t until three years later that my running interests were rekindled.

After the four or so kilometres along the little foot path the steep stairs are looming ahead. It’s just a little uncomfortable making my way through the overgrown bushes now wet with rain, trying to avoid the nettles stinging my legs as I climb the roughly hewn wooden stairs and ascend the little hilltop, my breath coming in short, noisy gushes. And down past the big cement ball, up another little hill and down again towards the park. The rain is relentless, but the spirit cannot be dampened. Specially not a runner’s spirit.

Just before turning twenty I joined a meditation course of the Sri Chinmoy Centre and visited a lecture given by a student of Sri Chinmoy from Austria, Nidhruvi. She had participated in a 700 miles race in New York and showed slides about this unbelievable endeavour. Here people were running not just for fun or fitness, but to grow spiritually and transcend their own boundaries. Something happened to me that night. At the end of the lecture I left the room full of inspiration and enthusiasm. I had another engagement somewhere else in town, about two kilometres away. I ran the whole way. Exhilarated.

The Hague is known for its parks. Including the dune area, the city has the most square kilometres of parkland in all of Europe. I like running in parks. This particular one has a nice loop which takes me about ten or eleven minutes. Puddles are everywhere, so I am forced to make a small detour. I’m now in that pleasant state of effortlessness, when the mind has become accustomed to the seeming discomforts of the repeated pounding and stops its tiny protests, which it often vents at the beginning of a run. Its silence is liberating.

My preparation for my first marathon is still one of the highlights of my running career. I was working in a restaurant in Paris at the time and the schedule afforded me ample time to train, which I did devotedly twice a day. My runs took me all across Paris, where I ran through practically every park the city owns. In those three months I probably saw more of Paris than many Parisians ever would. The goal of the approaching marathon gave my running a purpose and a meaning it hadn’t previously known. It was a joy beyond my imagination. A few months into the programme I could simply feel the oxygen pumping through my legs when I went down for breakfast in the morning, like a physical sensation. It was a revelation.

I love the rain, though. It seems to numb the senses until you are focused only on the essentials: how your legs are rotating, how your arms are swinging, how your breath is inhaling and exhaling. The rain brings me into the flow of running. What Zatopek said is true: ‘There's a great advantage in training under unfavourable conditions.’ I never skip a run just because it rains.

I had set my goal at two hours and forty minutes. The day of the race was a crisp April morning. I was one of thirty thousand, so I made sure to line up in front on the Champs Elysées. Three months of intense training leading up to one supreme effort. I was ready. The marathon took us through both forests on the outskirts of Paris, travelling along the Seine first eastwards, then westwards. It went well. Then the final ten kilometres came and I was in unknown territory. Everyone who has ever seriously trained for a marathon knows the feeling of these gruelling last ten kilometres. You cannot properly arm yourself against them. They always hurt. I remember almost crying with pain at the last two K’s. All sense of decorum leaves you if you are in such pain. You just don’t care anymore. Let it be over soon, your only thought. I finally crossed the finish line, almost astonished that it really exists. The chronometer says 2:45:30. A warm, unexpected shower of joy washes over me. I did it! I am a marathon runner.

The last part of the loop is empty of puddles, so I can still run on soft forest paths for a bit. Rounding the last bend there suddenly is a glow in my heart that seems to swell. I find myself gliding into the elusive and ever-coveted state of consciousness called the ‘runner’s high’. Endorphins from the brain are released, causing an exalted feeling. But much more than just a biological change in brain chemicals, my experience now soars beyond just a pleasant feeling and enters into the spiritual realm. I feel like all the elements of my life are suddenly brought together in one concentrated form. And I see myself as the co-creator of that form. It is as if God is showing me: this is your life. We are building it together and it is a good life. In that one uplifted, eternal moment there is no dark or strangling thought. I am one with my soul and life is its divine journey. So this is freedom, inner freedom, real freedom! I feel only joy and gratitude as unending possibilities and opportunities stretch before me in the uncharted future ahead. Things will be good there, I know. Not only for me, but for the whole world as well. It is in rare, golden moments like these when the inner runner and the outer runner shake hands that I understand the oneness between the two. Running is my sacred space.

Abhinabha Tangerman

The Hague, The Netherlands

I have been jetting about a lot lately, travelling to some lovely places. I visited Seattle, that wonderful city of trees and gardens and vistas of water—we had some meditation classes each evening and uncluttered free days of exploring. Some mornings in Seattle I wander down streets of flowered embankments, colourful and scented gardens, to breakfast at Zorba’s internet café. Here laptops rule—in a room filled with people, no-one talks, each intent in their own private world. I pull out a notepad and pen—outrageous anachronisms—and scribble a few things, then spot last week’s crossword puzzle on a newspaper stand. An animal plurals quiz. A --- of quail. Covey! A --- of owls. Parliament! A --- of geese. Easy. I fill out the wrong answers for fun. Pod of lions. Gaggle of ants. Sacrilege of swans. Covey of kittens. A quorum of crows. Actually it’s a murder of crows—amazingly—and I remember seeing assassin crows once behave in a way to warrant this phrase. A suggestion box is at the door and I scrawl, perhaps unkindly, ‘Coffee 7/10. Atmosphere 1/10. Ban laptops—reintroduce speech’.

Now an onward ramble past charming small houses and towering trees to Green Lake, three miles in circumference and its loop walk filled with locals on bikes and hundreds of prams. Is it a Mothers Day outing? A sea of prams. A clutch of prams? An apprenticeship of prams? Pitfall, I think. Anglers thrash the lake for trout, one hooking up in the willows behind him. One hundred meters further along, safe from the lures and fly rods, dozens of happy fish are consuming bread flung by excited children. Is it a tribulation of trout? A treason of trout! A titillation of trout?

Sri Chinmoy was in San Francisco on this day—on a television show his host asks him, what single message do you have for our audience? ‘That every human being is a very special dream of God….’

On now to New York and an evening outdoors of meditation and music with Sri Chinmoy. In the interludes between Guru’s songs sounds of other lives come in—across in the neighboring houses the gaiety of a party fills the night, Latin American dance music, an exhilaration of drums and elated trumpets, hands clapping their pleasure. They are dancing to an Andean song, pan flutes, the distinctive music of Peru with its signature tinge of poignancy that captures the knowing of its people—that sorrow is woven in with joy , impermanence woven into the sweet hours of celebration. They seize the night, wring out every little joy.

One week later I am flying across continental Africa en route to Johannesburg. From seven miles high everything of Africa seemed parched and dun-brown, the map of patchwork landscapes cluttered with its long human history, gouged by the yellow wounds of mining, gutted valleys from the gold boom and mountains torn down into symmetrical cones of slag, electricity cooling towers like giant convex pottery. Here and there Lilliputian settlements, the variegated circles of agriculture like widening raindrops, ragged empty fields and the scratch lines of pointless roads. Then further east vistas of ranges, bony upthrusts—the jutting rib cage of the earth—and everywhere fires burning, mountains burning, their lazy undulating plumes of smoke almost motionless, one sickle shaped front of flames stretching all the way to the horizon, a vast bonfire of forests and farmlands billowing up into columns of roiling grey that snaked away into trailing serpent tails. Until everything was swallowed up in smoke, Africa burning like Doomsday.

In 1879, down there somewhere the Zulu tribes taught the expeditionary British troops a painful lesson in military tactics and humility, massacred 1300 of them though armed only with spears.

Down there somewhere too, supposedly, the very genesis of everything, Africa a crucible of life and a wastepaper basket of discarded species. Forgotten things spawning out of the primordial pre-Cambrian seas, the crosshatching of algae, bacteria, diatoms, phytoplankton, cyanophytes, building blocks of the great evolutionary explosion, nutrient rich swamps and marshlands the nurseries of fantastic life forms, cellular couplings, genetic alchemy seething with possibilities.

Man’s first ancestors roamed these horizonless landscapes of veldts and wide valleys, grunting brutish things, Australopithecus ramidus, homo erectus, homo habilis, the hominoidea. Fast forward five to ten million years and here we are, the apex of it all—oh gosh!

Other theories though—earth populated by reconnoitering aliens fleeing their doomed planet (sound familiar?). Or creation theories, Adam and Eve, a seventh rib, Eden. Or a crashed intergalactic spacecraft, gooey plasmic life forms morphing into humanoid shape. But looking down at Africa burning, smog, desiccated plains, skies choked with smoke and soiled seas, the doomed planet theory is not implausible and Richard Branson’s pay-to-go space flights—are our elite and wealthy already heading off?—may open the floodgates of an exodus.

Our sacred spaces are under siege and it’s very depressing. I’m glad we’re not flying over the Brazilian rainforests—I would have an attack of petit mal and have to lower my window shade, refuse to look, watch some idiotic flick on my mini-screen while we slide over the Amazon, that Wild West of gun-toting grileiros and bandits; chainsaws and bulldozers; corrupt officials; illegal soya farms; illegal logging; illegal cattle farms and ranching; the great Brazilian wilderness that produces 20% of the earth’s oxygen disappearing to the extent of two hundred football fields every thirty minutes. And those other continents, the polar caps, shattering like restaurant china and downsizing while you sleep, the last white bears floating away on shrinking remnants of pack ice, too far to swim back.

But enough of that. My sister-disciple, Toshala, has entrusted me with two small boxes of her legendary caramel walnut slice as prasad for the South African Centre. Even the resolve of sadhus and renunciates would be tested by this maddeningly delicious concoction. Mysteriously the neat gooey wedges seem to shrink a little each day before Wednesday meditation—someone’s resolve has faltered. In a landslide of self indulgence and by mutual consent we agree to eat half the contents before the meditation evening and leave the rest till the hallowed evening comes. A joint conspiracy. Alone in the house while my hosts are at work each day, I have to summon what sense of fairness and moral rectitude I possess to restrain myself each time I open the refrigerator. There they were, the survivors, pale caramel brown in their clear plastic box, beckoning, beckoning.

During our Wednesday night meditation we have Sri Chinmoy singing a lovely song on a CD recording before we take prasad and I commented: “Guru once said that his music is bringing down to earth something that humanity has never had before”. Then we all sang a number of songs, some a little discordantly, and Abhijatri said, “When we sing we bring down to earth something humanity will never want again!” “Hush,” said Balarka “or you’ll forfeit your piece of caramel walnut slice”.

A week later I’m home bound and in transit in Singapore’s Changi airport. An addicted shopper might rate this much vaunted central shopping hub as a sacred space—blasphemy, yes, but no-one knows your secret thoughts. Armed with fistfuls of cash and a long in-transit time you could be happily distracted here for hours, wandering the gauntlet of enchanting things, clothing and confectionary stores, shop after shop of tauntingly inexpensive watches, gadgets from a new wave of I.T. toys, jewellery and liquor, internet cafes, luxurious rest areas jostling with decadently comfortable chairs where giant TV screens relive football's greatest moments. A shopping misfit, I sit in a chair and count my money and my possibilities. To be in the last third of my life and almost destitute in this great mecca of worldly joy, I should feel depressed, but don’t. With twenty Singapore dollars left I must choose between two slices of Pizza Farcita Vegetarina, a fresh O.J. and a cup of chamomile tea or a three hour snooze in the in-transit hotel—pay by the hour. The pizza easily wins.

Then to wander to the extremity of one of those great long departure wings that radiate out like the arms of an octopus from the hub of the Great Shops. Here I discover I-Squeeze—a wonderful mechanical foot massage—and surrender up both feet into two inviting velvet lined pockets. Press the ‘Go’ button and now you’re in Heaven, an army of strong but solicitous knobbly hands pummeling, kneading, squeezing, massaging while you restrain yourself from crying out ‘Aaah, mmmmm, oooooh’ in delight. I doze, then wake up to discover my feet have been overdone, looking red and pockmarked with indentations.

On the eleven hour haul back to Auckland a happy, surprise upgrade to business class. The woman on my right whispers to her husband “He’s not really’ business’—just an upgrade.” “Upgrade” as in leper… Flight attendants pander to our every whim while the cattle-class behind us, ten per row, groan and endlessly reposition themselves in their solitary confinement, economy class cells. We crossed the dead, ‘red-heart ’of Australia in daylight, this ancient eroded continent, mountain ranges drowned in sand, their peaks almost submerged; and occasional meteorite craters, the unmistakable pockmarks of old impact sites, some a kilometer wide. Further on, swirls of parallel ridgelines like the wrinkles in a large vat of cooling fudge, then grey and orange-brown desert. Occasional roads ran seemingly nowhere, like a stick trailed across the horizon, random pencil lines that seemed absurd in the barren emptiness. Further again, vast tracts of roadless forest, more random fires and a succession of immense braided rivers, waterless, the dessicated arteries of the earth, then near the coast the lovely floral veins of tidal catchments, a halo of capillaries lined with pale mangroves.

We cross the Tasman Sea as night falls—at last Auckland looms, the city smoldering in sullen light like a lava field. Three continents in three weeks. Sadly our sacred spaces and places are imperiled and all of mankind seems to be rushing headlong into a crisis of survival. The enormity of this tugs your heart. Yet the dinosaurs ruled this earth for almost 200 million years before God’s patience ran out—we, a more recent experiment have only been here 5–10 million years, a mere geologic second. Perhaps we can still get things right. God, will You please be patient a little longer, will You give us a little more time?

Jogyata Dallas

Auckland, New Zealand

Photograph: Sri Chinmoy Centre Album, South Africa

“Crossing a bare common, in snow puddles, at twilight, under a clouded sky, without having in my thoughts any occurrence of special good fortune, I have enjoyed a perfect exhilaration. I am glad to the brink of fear… Standing on the bare ground, — my head bathed by the blithe air, and uplifted into infinite space, — all mean egotism vanishes. I become a transparent eye-ball; I am nothing; I see all; the currents of the Universal Being circulate through me; I am part or particle of God. The name of the nearest friend sounds then foreign and accidental: to be brothers, to be acquaintances, — master or servant, is then a trifle and a disturbance. I am the lover of uncontained and immortal beauty...In the tranquil landscape, and especially in the distant line of the horizon, man beholds somewhat as beautiful as his own nature.”

—Ralph Waldo Emerson, from “Nature”

I remember stumbling upon these words of Emerson as I was thumbing through one of my younger sister's high school notebooks. The author was not listed on the page and it was years before I actually confirmed my suspicion that Emerson was the author. I remember being awestruck by its simple honesty and beauty. Emerson was saying that divine consciousness is as close as our own life breath. That spirituality or religious feeling is not a matter of belief, of doctrine. It is a matter of personal experience. I immediately borrowed the sheet of paper to photocopy it so I would have my very own copy of this immortal passage. I was never a serious scholar of classical authors and I was not one to fathom the mysteries of poetry. But the breathtaking beauty of this passage stopped me in my tracks. I was excited to see such a vivid expression of mystical experience. It was as if Emerson's soul surged to the fore in solitary moments in nature.

I cannot recall, ever in my life, having any such wilderness mystical experiences, but simply being a sort of a mystic myself, I recognize the feeling and partake of some tiny measure of that bliss every time I immerse myself in nature. Like many spiritual seekers, I vaguely remember moments of mystical experiences during childhood. Usually sacred moments sneak up on us when we least expect them.

Something about the fragrance and fullness of the great outdoors reaches into every crease and crevice of our consciousness and flushes out the trivial. Even if you do not consider yourself a woodsy person, you cannot help but be affected by the smell of the earth, the quiet softness of natural sounds and smells. Mundane worldly thoughts fall away.

“Nature's beauty helps us to be as vast as possible, as peaceful as possible and as pure as possible.” Sri Chinmoy

We feel somehow part of the universe rather than a desperate creature fighting against forces beyond our control. We remember that there is a flow to all of creation, we are part of the web of life. The universe cradles all of humanity and part of our role is to allow ourselves to be cradled. If we can just let go.

While in the wilderness, we may have a greater likelihood of mystical experience. Other times, a physically challenging event such as an ultra-distance athletic event can push us into that zone where we have a sense of transcending our normal levels of awareness and experience a glimpse of something that might be called bliss.

One such incident occurred about 10 years ago during a 12-hour walk staged by the Sri Chinmoy Marathon team. This walk was part of our April gathering of Sri Chinmoy's students from around the world for 2 weeks of meditation, performances and athletics. In particular, the 12-hour walk is an offering of self-transcendence, trying to go beyond one's personal comfort zone and walk as many miles in 12 hours as possible.

I had been strolling along at various speeds for at least 8 hours, maybe more. Things were at the stage where my physical capacity was pretty much wiped out. I was not in any danger of injury, I was just stiff, sore, aching, etc. everywhere. In other words, I was thoroughly uncomfortable. This is where the real self-transcendence begins...to persevere when it is no longer comfortable to do so.

Suddenly and without any expectation of “good fortune,” I found myself having the most amazing sensation: I felt very clearly that my usual sense of myself....that is to say my ego, my outer personality, whatever I usually think of as me, felt as if it had been removed and it was just following me off to my right side, and what was left was my soul and my body. The message that came to me was that “my body was following my soul.” I felt a tremendous sense of effortlessness and freedom. Not necessarily that walking was easier, though it may have been for those few moments, it was more that “existing” was effortless in that state. I was suddenly “made aware” that I was living in a habitual pattern of over-striving or trying too hard in day-to-day life.

In this moment of egolessness everything was so easy, so free, and I remember thinking that I wanted to feel that way all the time.

This extraordinary experience came about because of the extremely sacred atmosphere that pervades our twice annual spiritual gatherings, especially strongly felt during these self-transcendence events. I am grateful to my spiritual teacher, Sri Chinmoy, for the constant inspiration and encouragement he has offered me.

Terri Carr

Tampa, USA

I don't know why it took so long to give my first meditation class. My first article on meditation was written mere months after becoming a student of Sri Chinmoy’s, published in a national broadsheet for high schools, and in the years that followed, I wrote many more for newspapers and magazines, with something near ease.

Yet actually talking about meditation, without shield of pen and paper, never quite happened. Sure, I went to a thousand classes given by others. In fact I was almost certain I knew the ABC’s of meditation backwards, long audience to their exposition—possibly better than some of my fellow conversants. Quite the backseat driver, never quite managing to take the wheel.

I am not precisely sure why it took me so long to bite the apple, talk about it too. Me, the person who had once wiped the floor with opponents in a school debate; won a minor role in student politics solely on the back of an impromptu, unscripted speech; somehow, some why frozen for words at the thought of facing a room full of strangers, teaching a topic I knew so well.

Fate however forced my hand, without my intervention or even encouragement, a lecture series organised by a friend in the distant, outer suburbs. This friend was not, shall we say, a comfortable speaker. Fait accompli you could say.

In a spirit of resignation, and trepidation, I began preparing for the class, reading and then rereading Sri Chinmoy’s classic book on meditation, Meditation: Man Perfection in God Satisfaction. And taking several pages of notes, the first time since my days at university many years before, occasional nightmares ever since.

I had thought I knew the topic backwards, but I was wrong. Every page, paragraph and sentence of Meditation shed a new light on a daily practice as familiar as eating—if only as hungrily pursued! There had been a time when I struggled to reconcile the apparent simplicity of Sri Chinmoy’s writing with my own propensity for complexity; simplicity hides it’s depth from those who are too complicated. On the pages of Meditation, it seemed infinity dances between typeset words. Ahead of my first class, I was eager to learn every step.

The venue for the class was a hired room in a large suburban community centre. Amid the clink of cappuccinos, high-pitched scream of a coffee machine, muffled shouts and the repeated thuds of a basketball, I placed a meditation sandwich board on the ground and wondered if anybody would come. A part of me, the part suffering from nerves and anxious for words, was secretly hoping for the negative.

There was no time to examine, paint larger imaginary fears—heavy traffic had made my fellow lecturer and I precariously late, and we set to transforming the purple and white meeting room into a classroom for meditation; arranging chairs in rows, lighting incense, taking the “Do you have a problem with gambling?” posters down from the front of the room—we would be discussing a different type of fortune today.

We were about to call it a no-show when two did show: a flight of hair, perfumes, jewellery and tie-dyed blouses—a pair of middle-aged women straight out of a Shirley MacLaine novel.

To my secret appreciation, the only attendees of my first ever meditation class could hardly be called unforgiving. Were this a football match, you would say that I had the home advantage. Masters of re-birthing, channelling, auras and crystal healing, my lecture would be but a new aisle of the supermarket of spirituality for these ladies. They had heard of Sri Chinmoy, and were sincerely interested.

Politely avoiding a tour of their past lives, I started the workshop proper, an introduction to myself and the Sri Chinmoy Centre, as planned precisely in memorised notes.

Could it be that I was a captivating speaker? Despite prior reservations it did appear possible, for this audience of two was listening attentively, interest obvious, only too happy to talk about their meditation experiences. Self-doubt and fears about my capacity were proved solid as air.

The minutes passed, the incense burned, our breathing slowed, an all-encompassing peace filled the room, my heart as well. Words flowed through me as if carried upon crests of waves, and beneath the waves, an ocean of infinite stillness played. We had entered a sacred space. We were swimming in infinite space.

I don’t remember precisely what I talked about that day, and in hindsight, I doubt it even mattered. The truth was that somebody else gave the class, chose my words and guided the meditations, and I, an instrument in His skillful hands, was no longer highly strung, but rather perfectly in tune.

At the end of the hour and a half, although it seemed liked no time had passed at all, the students were effusive in their praise. “Yes,” they had had a “wonderful, very deep” meditations, and did I realise that I had “a most beautiful aura?” Ever the closet sentimentalist, I was secretly touched, but brushed it off with something witty and self-depracating.

Beautiful aura or successful lecturer, when it comes to myself, there is another who deserves the credit.

John-Paul Gillespie

Auckland, New Zealand

When I was 13 years old and in my first year at Mairehau High School, each week we gathered in Room 14 upstairs in the Cartwright Block—Miss Mann’s room. Miss Mann: the history teacher.

Miss Mann must have been sixty. She was one of the handful of teachers who wore her academic gown in the classroom, bedaubed with chalk dust, her old lady’s glasses sliding down her nose from her rheumy eyes or hanging on a chain around her neck.

Everybody else in the school considered her something of a silly old bat, but those whom she taught—they universally adored her. A motley collection we were—certainly not the best and the brightest—but captivated all by Miss Mann’s history class. Those of us who carried on to study history at the higher levels of the school and—heaven help us—even at university, found it a sad, dreary affair without Miss Mann. In those first two years at high school she followed, I am sure, no bureaucratically stipulated curriculum—she took us through the whole sweep of existence from the days when trilobites crawled on a primeval ocean floor to the day when, in the words of Sellar and Yeatman, ‘America became top nation and history came to a fullstop’.

Miss Mann viewed history as the story of our shared humanity, and like some ancient shaman telling the stories of the tribe around the fire, she passed on to us the stories of the events that had created our world. Carried away by her own passion she would be swinging her imaginary broadsword around the classroom, deep in some one-person re-enactment of the Battle of Bosworth Field as we sat captivated.

I remember Miss Mann telling us about the building of the great medieval cathedrals of Europe. She spoke authoritatively as one who had herself seen these things. How wildly sophisticated and cosmopolitan that made her in our tiny antipodean eyes! Vast they are, she said. So vast that when you are inside such a cathedral it makes you feel like an ant. ‘And who,’ she added, ‘wants to feel like an ant?’ Thus, in one stroke, she demolished the greatest architectural achievements of the Western world.

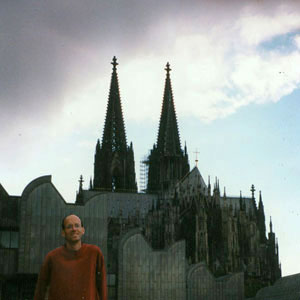

Nineteen years later I was driving with my brother down the autobahn from his house in Bonn. It was the day after Mother Teresa’s funeral in distant Calcutta. My nieces were in the back seat trying to be cool and certainly being very uninterested in going to Cologne again so that Uncle Barney could see ‘the Dom’.

We dropped the females out of the backseat that they might indulge in that bizarre feminine pleasure of shopping, and my brother and I headed for that mighty edifice, that vast outcrop of rock that dominated the skyline—the Cologne Cathedral, the Dom.

There are those who say that the Cologne cathedral is the greatest of the gothic cathedrals. In 1997 the interior was full of scaffolding—one could barely see the great gold tomb wherein they say ‘the three wise men’ lie buried—but still the building overwhelmed me with its vastness, its ever-ascending verticals soaring up to the very heavens.

That night I scrawled in my little journal of events—‘This is a more directly spiritual artform, more of a gesamptkunstwerk, more overpowering, more consuming than any building. It is like a piece of geography rather than architecture. I don’t doubt it is the high point of the European soul. It was climbing the tower, even more than looking from below, that gave one the impression of how large and how unified it was. “Unified” was the word that kept coming back—unbelievable profusion of imagination, eruptions of creativity, but unified, subsumed to a pure transcendent vision and upwards movement. It was rather scary climbing in the howling wind with the rain coming horizontal, but exhilarating to be climbing like an ant through and over a work of art—some unbelievably vast work orchestrated by some architectonic ‘mind of the age’ and, I guess, a few men in leather aprons.’

Ah, Miss Mann! Two decades later and there I was—the ant.

But stop!

We live in the post-colonial world. What is a man from the South Pacific doing extolling the irrelevant works of ‘dead, white males’ in the distant, alien lands of Europe? Here in our island nation where mighty rivers tumble down from rocky alps; where the blue sky domes wild tussock land and dripping rainforest; where waves that have not touched land for half a planet’s round, crash on kelp-clung rocks or sigh upon virgin sands; what need we with the puny works of man to find our sacred space? Walk out the door, man! Feel your spirit leap amidst the awesome splendour of snow-clad mountains, sweeping glaciers and tranquil alpine lakes; weep as the sun touches the bush and a solitary pair of putangitangi glide, honking softly, to rest among verdant undergrowth.

I have stood in the mountain fastness of the alps on the shore of Whakamatau and I have known why every nation has believed that God is in the sky. The sky is vast and beautiful and from it comes the sunshine and the rain that sustain our very existence. The sky is distant and mysterious and yet it is so close to us that it rests upon our skin. The sky is powerful and awesome and lightning strikes from it which shatters the rock and burns the land. The stars of the sky guide us as we travel through our life below.

All sacred space is sacred only in so far as it mirrors the sacred space that is within. So the wide blue sky resonates with the vast sweep of our eternal spirit; the ocean speaks to the vast, endless surge within. Fortunate are we here in our distant nation at the ends of the Earth who find ourselves in that temple whose dome is the vaulted air, where-in one kneels on the gentle sand and is baptised by the passing tide. One need but bring a flame with which to worship God.

The sky, the sea, the deep bush, the high mountain, the deep and labyrinthine cave—these are our sacred spaces.

Was there ever a rocky coastline caught between the never-ending sea and the immutable land that was not sacred? Did I ever scramble around the rocks, peering into the other world of rock-pool creatures and waving weed; wading from point to point; clambering over slick rocks and sharp shells and not know myself in a space that was sacred?

The temples of India are built around the garbha-griha, a windowless and sparsely lit chamber which few may enter, the womb chamber, which is the centre of the cosmos and the centre of the soul, the mysterious darkness from which flows all life, the cave of the heart, the place where the divine manifests in a tangible form, the axis of the temple, the axis of the world.

Beneath the vault of the sky we feel the vastness of God, but creep into a cave on some rocky shore; the waves at its mouth; the damp, dark of rock all around, and one is entering the first garbha-griha, more sacred than any built by man.

I have crept into caves on a rocky seashore and sat in the darkness.

I have dreamt of some ancient Celtic monk on a bleak, rock-strewn coastline, the grey waters of an angry sea roaring at the mouth of his cave and him lost within in the dark of that womb chamber in contemplation of the love divine of his gentle master, the love that holds all tranquil within its encompassing and abiding shelter.

The vast buttressed walls of the Dom in Cologne were, as the rain slashed down upon them on that September afternoon, like the convoluted cliffs wherein any number of anchorites might live; the wind was the howling of spirit, the great grey sky above, the very vault of God. Sacred space—everywhere.

Barney McBryde

Auckland, New Zealand

From the solemn gloom of the temple

children run out to sit in the dust,

God watches them play

and forgets the priest.

- Rabindranath Tagore, Fireflies

Our concept of sacred places conjures up images of a Himalayan cave, or an ancient Temple, befitted with a continued history of sanctity and holiness. But delving into the experience of great saints and sages we find a concept of the sacred can appear in the most unlikely of places.

Tagore himself was once lacking in poetic inspiration. He travelled to the silence and majesty of the Himalayan mountains, expecting the silence and sacred vibrations of the great mountains to inspire him. Much to his exasperation, he found himself unable to write even one word. Forlornly, he travelled back to the hustle and bustle of Calcutta, and it was here that his literary output returned with new inspiration. It was fitting that Tagore gained inspiration amidst the most ordinary of surroundings, for Tagore was a master of seeing the divine in everyday activities and objects.

It is the message of the Seers that any place can become Sacred, so long as we see the inner reality. In 1909, the celebrated Indian Yogi and revolutionary, Sri Aurobindo, was imprisoned by the British. He spent countless hours locked up in a tiny cell. For man, prison is a symbol of everything that denies freedom; it is an instrument of oppression and suffering. Jail is perhaps the last place we would expect to encounter the Divine. Yet, here in his tiny prison cell, Sri Aurobindo witnessed a profound and lasting mystical experience which enabled him to see God even within the bars of prison.

“I looked at the jail that secluded me from men and it was no longer by its high walls that I was imprisoned; no, it was Vasudeva who surrounded me. I walked under the branches of the tree in front of my cell but it was not the tree, I knew it was Vasudeva, it was Sri Krishna whom I saw standing there and holding over me his shade. I looked at the bars of my cell, the very grating that did duty for a door and again I saw Vasudeva. It was Narayana who was guarding and standing sentry over me.”

—Sri Aurobindo, The Uttarpara Address

To Sri Aurobindo, his cell manifested only light and the presence of God (Vasudeva). Through soulful meditation his cell had been converted from a place of hell, to a holy sanctuary. To experience even a glimpse of that in our churches and temples would make the visit most unforgettable.

Sri Aurobindo is not the only person to have a feeling of the sacred in jail. Many centuries earlier, St John of the Cross, was imprisoned by priests who were jealous and fearful of his mystical revelations. Yet, St John of the Cross testifies how his days passed intoxicated with the consciousness of God, even amidst the direst of circumstances and tortures.

In the nineteenth century, a young, uneducated French peasant described seeing visions of a beautiful lady in a grotto, at Massabielle. Her name was Bernadette Soubirous, and she would later become known as a great Saint and visionary of Lourdes. Yet, her visions were subject to the most stringent of criticisms. Not least, was the question, why would the Virgin Mary, Queen of the Angels, reveal herself in a dark damp grotto; a grotto that was used as a rubbish dump and place for grazing pigs? To this, Bernadette could only answer, had not the Lord Jesus been born in a stable? Yet, even those who perhaps doubted the visions of a young peasant girl, could not help marvel at the divine countenance of the young Bernadette, during her 17 visions. Reflected in her face was the intense ecstasy of divine communion. The experience transformed this small dumping ground. From being neglected and misused, the grotto has become a place of worship and pilgrimage.

One could give numerous more examples of saints and sages who have seen the sacred in the ordinary, and witnessed the divine in the mundane. They show us that a living experience of the divine is what makes a place sacred. To travel to sacred places is undoubtedly good, but to feel the sacred in everything is the mark of a real mystic and saint.

I have little knowledge of sacred places, and little time to visit them. But, for myself, a sacred place is Aspiration Ground, in New York. It is at Aspiration Ground that I have spent much time in the presence of my spiritual teacher, Sri Chinmoy. Aspiration Ground is another unlikely candidate that became a sacred place. Set in the heart of a busy New York borough, it was an old tram station, later converted into a tennis ground. Yet, for the past 20 years or so, the location has built up a meditative vibration of peace and spirituality. It has become an oasis of quiet peace and beauty, in the midst of the dynamism and concrete jungle that is New York.

Tejvan Pettinger

Oxford, England

Once upon a time, I was impressed by Notre Dame Cathedral.

There is much to recommend about this building. The achitecture is splendid. The carvings are beautiful, seeping with history. Visiting this revered and majestic place of worship, a respite from the shops and the coffee shops of central Paris, I was truly… underwhelmed. Yes, that was the word.

In fact, the only time Notre Dame Cathedral impressed me was when I read Victor Hugo’s The Hunchback of Notre Dame. As a child, I had already read quite a few novels, but I had never known a building to be described in such loving detail. Hugo waxed lyrical about “the immense central rose window, flanked by its two lateral windows, like a priest by his deacon and subdeacon” and “the two black and massive towers with their slate penthouses, harmonious parts of a magnificent whole”, which developed into “a vast symphony in stone, so to speak; the colossal work of one man and one people, all together one and complex.” To him, it was a human creation “as powerful and fecund as the divine creation of which it seems to have stolen the double character—variety, eternity.”

I couldn’t pretend to understand all of those words, any more than I would have understood the French from which they were translated. But I could pick up enough to know that Notre Dame was something quite special.

When it was written Hugo’s description—bemoaning the loss of the Gothic architecture of old—renewed interest in Notre Dame. Indeed, it ensured that the cathedral would not only be restored to its old brilliance, but would be preserved for the future. Sadly, no amount of renovation could bring back the inner beauty, which not even Hugo could aptly describe.

One hundred and sixty-eight years after he wrote his nostalgic glimpse of mediaeval architecture, I walked into a crowded cathedral. It was mid-week. None of the people present were priests or acolytes. None of them were praying, save for one woman in a pew near the front, trying to focus (with some effort, it was obvious) with all the noise around her. Three tour guides were there, each speaking different languages, each with a posse of tourists. The only other people were independent tourists like myself, but with cameras, which they were snapping away nonchalantly.

I’m a Roman Catholic, who actually used to attend mass regularly in my childhood, rather than avoid it like most of my friends. Nonetheless, when I visited Notre Dame, I didn’t get the feeling of grace that I have discovered in several Buddhist and Hindu temples over the years. After all this time, worship is no longer Notre Dame’s sole purpose, or even its main purpose. The carvings and the architecture, exquisite as they are, have almost no meaning. The feeling of God—that being or sensation or entity that can only be felt, not analysed in all our mental arrogance—is more apparent in the modest church I attended in my childhood, or even in that small part of my room that I reserve for meditation. Notre Dame, sadly, is now the victim of its own success. Like many human beings who achieve name and fame, it has sacrificed something of its heart and its inner wealth.

A few years later, I visited the Shwedagon Pagoda in central Rangoon, then the capital city of Myanmar (or Burma, as it is still known to most westerners). The central spire jets out brilliantly, a stunning structure of white and gold, ensuring that Shwedagon marks Rangoon just as the Eiffel Tower marks Paris.

Walking along the marble floors of the Pagoda, you see countless statues of the Buddha in meditation, which might or might not resemble the real man. No surprise; this is the norm for Buddhist temples in South-East Asia. Of course, Myanmar is a special country for the sincere devotion of its people. I believe that Sri Chinmoy once referred to Myanmar as “the land of the Buddha’s heart.”

Still, whatever else they might have done, Shwedagon remains sacred, just as it has been for centuries. Sunrise to sunset, the people visiting Shwedagon still outnumber even the statues of Buddha. Like the statues, they are there to pray, to meditate. The devotion, the feeling of peace, permeates the air. Tourists go there as well, but as they are not visiting the sights of Paris, they are a different brand. Many of them are pilgrims, meditating with the locals. The others are respectful, at the very least. Even visiting with a camera, it seems amiss to use it—though you are certainly permitted.

With all the hardships of life in Myanmar, perhaps faith is all that the people have left. It is certainly their greatest asset—along with Shwedagon, the conduit of their faith. It might not be as famous as Indonesia’s Borobodur temple or Japan’s giant Buddha statue at Kamakura… but perhaps that relative obscurity is in its favour, one of the things that have left Shwedagon so unspoiled.

Writers can use all the words they like about the outer beauty of a place or a building, but they can never properly convey the inner beauty of some places. That’s when they helplessly use clichés—“inner beauty”, “tranquil surroundings”, “a certain magic”. We can never visit Notre Dame as it once was, in all its mediaeval glory, but other places—from the Shwedagon Pagoda to the old town of Istanbul to the rainforests of northern Australia—still have a sacred presence. In such places, something works, miraculously and unexplainably. It is not simply the outer frame, but the inner feel.

Noivedya Juddery

Canberra, Australia

I have noticed that good teachers of any subject- mathematics, foreign languages, or any other topic, are really good at creating a special space for instruction and learning. Of course, great teaching isn’t just about making a classroom attractive or putting up posters and quotations appropriate to the subject matter. But excellent teachers create an aura of enthusiasm and excitement for their subject, an environment where nothing matters except fractal geometry, Spanish history or playwriting.

When I was in third grade I had to undergo back surgery, and was partially immobilized in a torso cast. My third grade teacher, Mrs. Smith (not her real name) managed to integrate me effortlessly into the class flow. I don’t know how she did it. But she was really funny and really smart, and had a deep love for teaching. I hated studying and schoolwork before I had her as a teacher. I loved academics and the pursuit of knowledge after the third grade, however; she changed my life.

Once, I called this woman “mom”. All the other kids started to laugh, but my teacher interrupted them and said, “Oh, I’ve been called mom before. Let’s see here, it’s been “mom”, “grandma”, “auntie”, and one kid even called me”, and she paused for emphasis, “granddad!” And she scrunched up her face.

Everybody laughed and I wasn’t embarrassed at all.

I remember her class as being full of light, open space, perfectly organized. But it wasn’t a sterile kind of organization. The books, children’s magazines, mircrofiche equipment, and drawing and paper supplies were all placed to be inviting and accessible. It was a special place for learning. The perfect planning of Mrs. Smith’s classroom came from her affection for us, and passion for teaching.

In middle school, I don’t remember any one classroom that struck me as being special. It was actually the middle school building itself that sticks out in my mind. It was the oldest building in the township, I think, made entirely of brick. The hallways were made of dark, polished wood, and the floors were of thick, maroon carpets. I remember the library, especially, because of that thick, comfortable carpet, low ceiling and endless lines of shelves. A perfect place to lose yourself in a good book. It was an old building, faded and creaking, but that somehow added to its charm.

The course I most enjoyed in high school was known as “HELL” (History of European Literature and Languages). It was a course team-taught by an English and a History teacher. The classroom where the course was taught wasn’t special, but the understanding and respect that these two women had for each other was. Team-taught courses can often be boring and repetitious because the people teaching it don’t work together or don’t have much background in each other’s fields. But because these two instructors had taught this course for year after year, they knew how to make even the tiniest details interesting. It was a joy to watch them work together. They had established a sense of oneness, and involved all of us in a true bond of community.

Among the many wonderful college instructors I had, my philosophy Professor, Dominick, stands out. He was a simple, humble man whose knowledge of philosophy and religion seemed to defy all limits. People would often fall asleep in his class, not because his courses were boring, but because he had this incredibly soothing voice! I remember sitting in his class, feeling buoyed on this wave of peace, and then when the class ended I would sit for a little while afterward, as if I had just finished a wonderful, relaxing steam bath. His very presence was therapeutic. He told us once that he had been a Franciscan friar in his youth, and had maintained a four-year vow of silence. That seemed fit because he carried an aura of silence wherever he went; and even when lecturing or joking with us we could feel his inner peace and tranquility.

I have always been amazed at how my spiritual Teacher, Sri Chinmoy, can turn any place into a sacred space for learning, self-transcendence and spiritual aspiration. The first time I met him was at a World Harmony Concert he gave in my hometown of Philadelphia. It was held at the hockey arena. But he created the most other-worldly atmosphere of delight and joy that I have ever experienced. I’ve sometimes suffered from self-doubt and insecurity, but when I was in his presence for those two or three hours, I really felt my own divinity, the spark of Truth that shines in the depths of my heart as well as everybody else’s. And that’s the function of the great spiritual Teachers- to awaken us, to show us how we can have a better and more fulfilling life. Sri Chinmoy is, in my estimation, one of those rare souls who create sacred space wherever they go.

God has blessed my life with many remarkable teachers who have uplifted me and who gave me inspiration when I needed it most. I really can’t think of a better or a higher Grace than that.

Mahiruha Klein

Philadelphia, USA

Photograph: Kedar Misani

Our members

Stories

First-hand experiences of meditation and spirituality.

If a little meditation can give you this kind of experience...

Pragya Gerig Nuremberg, Germany

President Gorbachev: a special soul brought down for a special reason

Mridanga Spencer Ipswich, United Kingdom

An intense, concentrated Fire

Toshala Elliott Auckland, New Zealand

'I could find out myself, but it was so much easier asking your soul'

Mridanga Spencer Ipswich, United Kingdom

In the Right Place, At the Right Time

Eshana Gadjanski Novi Sad, Serbia

A Divine Phone Call

Jogyata Dallas Auckland, New Zealand

The Ever-Transcending Goal

Preetidutta Thorpe Auckland, New Zealand

Breaking the world record for the longest game of hopscotch

Pipasa Glass & Jamini Young Seattle, United States

Seeing the God inside my son

Utsahi St-Armand Ottawa, Canada

Why run 3100 miles?

Smarana Puntigam Vienna, Austria

The Impact of a Yogi on My Life

Agni Casanova San Juan, Puerto Rico

Sri Chinmoy performs on the world's largest organ

Prachar Stegemann Canberra, Australia

Sri Chinmoy meets an old friend

Pradhan Balter Chicago, United StatesSuggested videos

interviews with Sri Chinmoy's students

My first experience with Sri Chinmoy

Nayak Polissar Seattle, United States

How I became interested in meditation

Abhejali Bernardova Zlín, Czech Republic

Meditation: you make progress just by doing it

Jogyata Dallas Auckland, New Zealand

Spirituality - the most fascinating subject on earth

Laila Faerman New York, United States

Growing up on Sri Chinmoy's path

Aruna Pohland Augsburg, Germany

Humorous moments with Sri Chinmoy

Toshala Elliott Auckland, New Zealand

My spiritual search from childhood

Hemabha Jang Jeonju, South Korea

Except where explicitly stated otherwise, the contents of this site are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. read more »

SriChinmoyCentre.org is a Vasudeva Server project.